On 12th November Professor Kirsi Monni sahred her views on contemporary dance as an art form, the changes in its aesthetics and ideology in the XXth century and the current contemporary dance field in her lecture at ZIL Centre. ROOM FOR provides you with original text of the lecture and its Russian translation.

Introduction

I see that contemporary dance today is an art form that is intensely trying to develop further its’

self-understanding and self-reflection. This happens all-over in education, in international

seminars and gatherings, in research and in the works of art itself. What is it about this time we

live in, that demands such a discussion, and on the other hand, enables it? Is it just a struggle for

survival in the midst of ever growing production economy and precariat working conditions that

force one to be able to argument for the work and contextualize it in a scholar level? Or is it that

dance art is claiming more space and visibility in a media saturated internet society? That it

demands deeper understanding of its ontology as a container of complex webs of relations and

meanings, in the midst of a consumer culture, based on immediately identifiable products and

simplified opinions?

Deviating from the simplistic production economy, anthropologist Gregory Bateson emphasises

the complexity that art contains: “In artworks and their interpretation, it seems that rigid focusing

upon any single set of relata destroys for the artist the more profound significance of the work. [ ]

The art work would be trivial if it is about only one identifiable relata. It is non-trivial or profound

precisely because it is about relationships and not about any one identifiable relativity.” (Bateson

2015, 48).

In the production economy, the product contains and only brings forth identifiable relations, both

material usage as well as immaterial, imaginary values. But an artwork, on the other hand,

subverts this self-evidence, the usability, consumability; it introduces a network of relations that

cannot be controlled through complete identification; it brings forth subconscious, complex

mappings of relations, the stirrings of a readymade world. Anthropologist Mary Bateson states

that one reason why poetry is important for finding out about the world is because in poetry a set

of relationships get mapped onto a level a diversity in us that we don’t ordinarily have access to.

We bring it out in poetry. We need poetry as knowledge about the world and about ourselves,

because of this mapping from complexity to complexity. (Bateson, Mary 2015, 49).

I’m talking about discourses but how is the concept defined? Discourses could be defined as a

systems of related meanings, a body of text meant to communicate a specific data or a context of

communication. Discourses affect how the cultural and social order appears and is shaped in

different time periods, places and communities. Philosopher Chantal Mouffe states that art could

be seen as a form of material discourse. Discourses are internalized in the material practices of art,

in the performers bodily articulation, in the methods of practicing and creating. But discourses

concerning art exist also in speech, images and textual level. Therefore, we can say that discourses

in dance are not only material or linguistic, they are both, existing in various levels of practice,

theory, everyday actions and dance’s relation to society.

In this talk I try to analyse some key features of the changes in dance aesthetics during the last

decades and articulate some of that complexity that dance as a material discourse contains in its

manifold manifestations. I see the current dance scene as a field of multiple discourses and

heterocronic, simultaneously operating time layers. I attempt to understand those multi-layered

interests that present day dance makers seem to have and formulate some conceptual

articulations on them. This is in order to be able to contribute to the cultural discussion, not only

by means of art, but also by means of language and speech.

In these times of heterogeneous aesthetic aims if we try to answer to the question of evaluation

and quality of art from the viewpoint of presumed sameness of universal, homogenous aesthetic

values, it seems to do injustice to the manifold of works of art and artists. Rather it seems often

more proper to ponder the credibility of individual artistic processes, the relevance of artistic

questions and methodical approaches in each context. Consequently, the ability to situate oneself

within these discourses is increasingly crucial for artists but also for students of art.

Main lines of the evolution of contemporary dance since 1900s

The evolution of western contemporary dance art, its aesthetics and ontology, was intense and

expanding throughout the last century. The general line of this evolution could be described as a

gradual separation from the traditions of classical ballet to the developments of modern dance

since the 1920s and to the postmodern and contemporary dance since the 1960s. Further on, the

deviation from modern dance and the sub-genres of contemporary dance could be labelled for

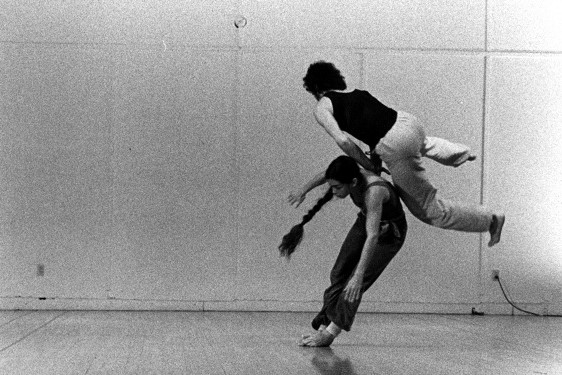

example as the “choreographic materiality” of the non-representational dance of the New York

avant-garde scene of the 1960s, the outburst of the somatic practices in the new dance of the

1970s, the fragmented dramaturgy and addressing the audience in the dance theatre of the 1980s,

the refusal of using any generic choreographic language, the exhaustion of movement and the

conceptual dance of the 1990s, and the deconstruction of the performing identities in the so

called performative dance of the 2000. All these phenomena are of course intertwined with larger

discourses in society, politics and philosophies. Therefore, written or oral history of dance, or the

analyses of the present day, depends heavily on the chosen perspectives of the interpreter and no

comprehensive or total narrative could be presented, just partial views on the issue.

One possible view to interpret the present day is to examine the various representation modes

that dance has typically used in its world-relation, in certain eras, or within certain ideas

concerning the ontology of art. The first profound analyses of the representation modes in dance

was informed by semiotic reading by Susan Leigh Foster in her research Reading Dance. Bodies

and Subjects in Contemporary American Dance. (1986). The modes of imitation, replication,

resemblance and reflection were placed within the era of their typical use and linked to the larger

cultural histories. If for example the replication mode was typical for the expressive and symbolic

modern dance era, the resemblance was typical for the somatic and perception practises based

dance, the reflection mode was typical for the abstract postmodernism informed by the

phenomenological minimalism.

Within the limited time frame of this talk, I chose to continue now in presenting an overview to

the contemporary dance scene from the perspective of somewhat opposing dialectics. This is due

to show how varied and heterogeneous the artistic aims are and how sometimes opposite their

aesthetic values can be. Different genres or artistic aims carry diverse genealogy in their

constitution, they relate to varied phenomena and era in dance history and take part to diverse

discourses in culture and society. The historically evolved features of dance have served in the

time of their emergence certain artistic vision and worldview and contained certain views to the

issues of for example representation, composition, dramaturgy, agency, identity, ontological

insights and categorizations concerning reality. One can and maybe should ask whether those

notions or terminologies are still accurate and whether they serve properly one’s artistic aims, or

does one need to revise the methods as well as terminologies in order to highlight the current

themes.

Some interpretations of the dialects in the contemporary dance performance

On the one hand we have the ancient idea of the pedagogic and indoctrinating mission of dance,

of which most prominent manifestation is handed down to us from the Baroque period of the

17th Century. Besides to achieve certain aesthetic realm, the purpose was also to create a subject

that maintains harmony and order in society, an obedient body. We are talking about an identity

that is thought to be permanent and whole and which is choreographed and maintained by

carefully constructed styles, techniques, bodily habitus and vocabulary.

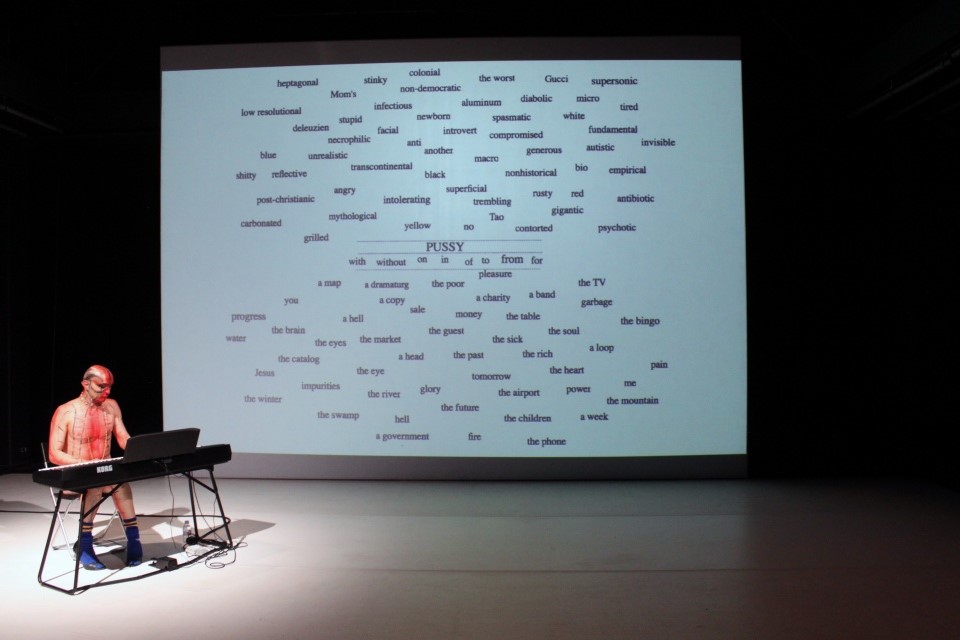

In opposition to this we can see the conscious striving, by the end of the 1900s and early 2000s, to

continually redefine the subject, to explore the performative power to deconstruct and construct

identities by way of addressing the embodied cultural discourses in live performances.

On the one hand we have the idea that is linked with the kinetic ideology of the modern era, the

constant move forward, an idea that dance as an art form is defined by the continuity of

movement, a certain kinaesthetic imperative, that dance is dancing, that there is an ontological

identification of dance as an art form, the choreography and the continuity of movement.

On the other hand, we can see, as a countermovement, the criticism towards the ever

accelerating kinetics of modernity and the homogenizing production economy, criticism that

appeared as motifs of stopping the movement and introducing the individual subject. This is aimed

at also to the separation of the choreography from the continuous and generic “dance

movement”. Dance art started to be seen as a means to explore the choreographed world as such.

Therefore, the theme of the choreographic study could be for example how bodies, subjects,

values or meanings are choreographed by habits, ideologies, economies and politics.

The question of choreographed societies and subjects could also be explored by studying how we

see the legitimization of the dancing subject. On the one hand we see that the acceptance and

credibility depend on certain technical dance skills, an established movement technique or

virtuosic control of a style that is achieved by years of hard practice and devotion. This achieved

skill opens up possibilities of expression and passing on the tradition which is not possible without

it. Within this lineage the quality of movement and the dancer’s skill differ greatly from those of

everyday movement and non-professional individual. In this context the “amateur body” on stage

is hardly considered proper in this material discourse.

But since 1960s and gradually in larger extent, this notion has been expanded. The separation of

the choreographic and the virtuoso movement, the deconstruction of permanent identities, the

critique of the society of the spectacle and the notion of social choreography have opened a wider

space for artistic expression. There has emerged an understanding that the dancing subject, in

his/her individual bodily articulation, is expressive in artistic sense and the acceptability or

credibility of the dancing is seen as an issue of defining the context of each performance, the

relevance of the methods used and the relevance of performance dramaturgy.

How about then the legitimacy of choreography if on the one hand the notion of dance art is

tightly woven with the skilful dancing subject and on the other hand, the choreographic subject

can be any individual, situation or even a framed system in a certain performance context?

Knowingly simplifying this question, I see that especially within certain, more established or large

audience contexts, some formal features of “a good and credible choreography” could be defined.

Such as the handicraft quality of the movement composition: the aesthetically unified movement

language, the consistent development of the movement motifs, the homogeneous performers,

the choreographic complexity, the inventiveness of the movement vocabulary, and finally the

coherence and the un-problematizing dramaturgy of the compositional whole.

But when artistic study sets its starting point in a wider quest of exploring the choreographed

world as such, it has to find and define its particular themes, methods and relationships to

representation and composition anew in each time. This situation reminds the situation familiar

with for example in contemporary fine arts, where each individual artist defines her/his

relationship to art history, and each work of art is a singular process of artistic research within the

medium, its material, practices and conventions. So how to understand these choreographies and

where to situate them?

I suggest that the choreography can be viewed as a tool to explore and

unravel corporeal world-relations and material discourses in art and society.

The legitimacy or credibility, (if one wants to use these kind of valuing operations at all) could be thought of depending for example on the relevance of the artistic questions, the used methods, the web of relations that the work brings forth, the contextual awareness and the articulation of the

performance event. Instead of fulfilling the preconceived ideas of choreographic continuum, the

composition might need and use strategies such as aesthetic discontinuity, heterogeneous

motives and performers, decentralized dramaturgy, interruption, emergent and systemic

structures and scores, “intertextuality”, multiracial consciousness and contextualized relations to

processes and materials.

And finally considering the role and position of the artist, we have the established notion of the

relationship between artist and artwork: the individual artist is the auteur of an original work of

art, she/he owns the work of art, and this ownership determines the value of the artwork in the

art market, depending of course how the artist’s production has been ranked in value in the fields

of art.

An opposing practice would be for example the collective creation of an artwork, shared

auteurship and joint ownership of the artwork, open access distribution of the choreography, free

entry performances, social choreography projects etc. All these features cause difficulty in

determining the market exchange value of the artwork or the artists in the field of art. And it is

necessary to remark that these practices get rather quickly appropriated by the market in such a

way that the ’creativity’ of the artist, even when jointly perceived and legitimated, does not yet or

necessarily strengthen the position of the artists themselves.

To conclude this chapter of my lecture, it is thus my understanding that the field of contemporary

dance is characterized by the diversity of approaches in which hardly anyone, would identify

themselves fully with the dichotomies I listed but find themselves in various relations to all these

factors. Rather than assume sameness among the dance artists, the present day dance field is built

with ontological and aesthetic differences and parallelism.