It’s been 15 years since the founding of PO.V.S.Tanze, a company that’s been an essential part of contemporary dance in Russia.

The day before the anniversary we had a talk with the co-founders of the company Sasha Konnikova and Albert Albert on the recent period of change, critics’ reviews and audience response, and some extraordinary people engaged in this 15-year life.

Translated from Russian by Yana Lebedikhina. Original text in Russian was published by ROOM FOR on the 30th of April, 2014.ON TRANSFORMATION

Katya Ganyushina (KG): We’ve been watching the recordings of your performances and felt like a profound change had occurred to you at some point. For instance, “ShumZo” performance is completely different from what you were doing in 2008. It seems like 5 years ago there was a really tough kind of search that made sense to nobody at all, but you knew you just had to get through it. Does it resonate with what was happening to you at that time or is it just what it looked like?

Albert Albert (AA): It’s nice to hear that you felt there might have been a difference. The reasons are plenty; I’ll just point out a few. I think all of us involved in something to do with contemporary, whatever it is, took a great deal of trouble to keep up with what was going on around, whether in Russia, Europe, or the USA. How is it happening? What’s cool? What’s fun? What catches our fancy? Consciously or unconsciously we were being hugely influenced by certain things, and remained under this influence for some time. We might have even wanted to be like something, or there were things that inspired us. After some time this connectivity, or preoccupation, somewhat waned. I mean, the desire to cling to something, to fit into a context, to catch the train that hasn’t started to move yet.

KG: And how did that change happen?

AA: How did it happen? Well, I can only speak for myself, and might still be wrong. I got fed up I guess. We just stopped bothering about all that stuff, conforming to something, playing all those games with the society etc. We lightened up on being associated with any kind of so-called contemporary art or contemporary dance institution. At some points we got glimpses of a different picture, and that made us loosen up a bit. It had an exhilarating effect on us, a sense that “we don’t have to” and an understanding that bliss can last forever. And although it was an illusion, it was still enjoyable and enticing, a real empowerment to us. By that time some new people emerged, new faces we were excited to walk along with, work with.

It’s hard to find, I mean it. Things like arriving to appointments on time.

KG: Can you say the names of these people?

AA: Absolutely not, they are very mysterious figures (laughing). Surely we can.

Sasha Konnikova: Ilya Belenkov and Alexander Andriyashkin.

AA: They were hearty guys that emerged from Siberia, which also matters, unspoiled by ideas of the capital city, and with an intense desire towards it, an aggressive one. And we were overjoyed, as they were really extraordinary people.

SK: … quite extraordinary, yeah …

AA: They’ve always been very responsible. It’s hard to find, I mean it. Things like arriving to appointments on time, being responsible for their words, their acts, respecting what they or others do, their time as well as that of other people. They’ve been great in terms of this! And there was a young girl, Sonya Levin, unusually mature for her age. Those were the new people we did a few works with, the works that mean a lot to us.

SK: The transformation we’re talking about started off, as we see it, in 2008 with the work “Days&Nights” (“Nochi i Dni”). The transformation was towards the idea that nothing maters except for your own interest and your trying to resolve your own issues inside the story we call contemporary dance. We used to make sure that each subsequent dance was different from the previous one. Every time we challenged ourselves, put to the test how free we could be. Apparently, since 2008 this attitude has somehow dissolved. Our dances might turn out to be different, but it’s not because we’re challenging ourselves, it’s just that something else has come up. A need for the next question arose.

KG: Sounds like up to 2008 you had been mostly fuelled or motivated by that challenge you had set up for yourselves …?

AA: I don’t think that’s what fuelled us best.

SK: Well, surely, I guess the overwhelming need to create must have been the case.

AA: I think we might need another couple of years to be able to answer your question about our key motivator. We’re still wondering what it was that drove us. But that challenge definitely counts, too. It had to do with a sort of understanding of how to stay in shape as an artist.

So here we are lying on the floor, and we hear the wave rising, people standing up from their seats to check out what it’s all about, wondering if we’re all right.

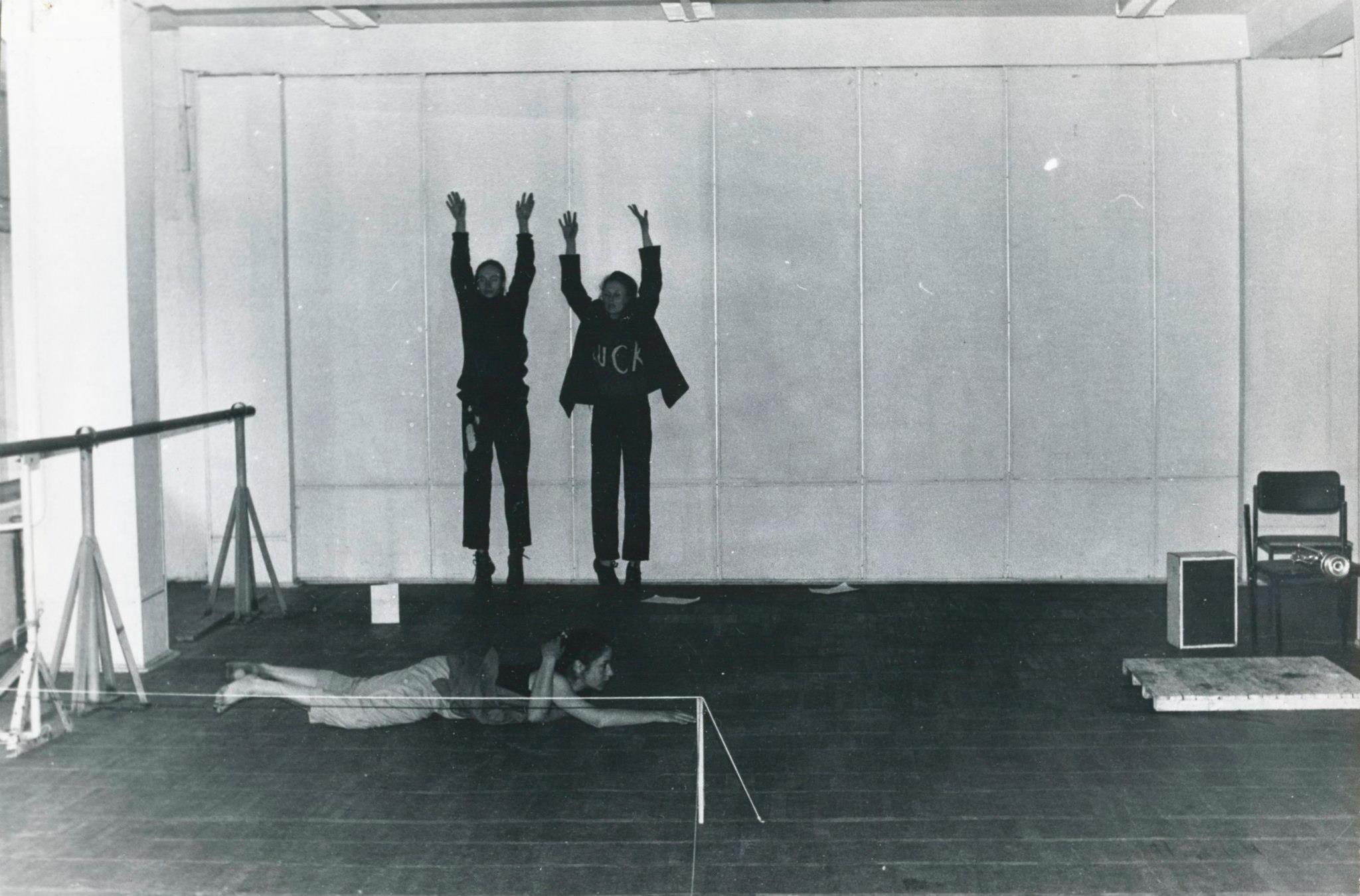

SK: It reminds me of an improvisational performance where at some point everyone had to come up to the microphone and say “I am a bad dancer”. And it had to be said sincerely… That was the flip side of the thing we are talking about… In “Days&Nights” performance there had already been a personal research, but the challenge had still remained. It was a sort of transitional period. And that performance started with us lying still on the stage for 3 minutes …

AA: … we were just lying still for 3 minutes. And that was an odd experience. We knew beforehand that the piece would be premiered in Kostroma, not Moscow, so we knew that the audience would be innocent in a good way, not that much spoiled. And so here we are lying on the floor, and we hear the wave rising, people standing up from their seats to check out what it’s all about, wondering if we’re all right.

SK: … and we keep on lying still, having our own issues at hand, while people are gradually growing more worried. And then 3 minutes are gone, and we start moving, while people start calming down. And it feels like an act of theurgy. That’s what the performance was about, and it was all happening, but it surely still contained a challenge. We also brought “Days&Nights” to Kirov, with a really positive after-talk with the audience, and in the end a lady shoots a question, “Well, after all, was there any plot in that piece? What was that performance, that duet all about?” And I just felt like saying: “Surely it was about a couple, a family! They sleep, they wake up (see, the title is “Days&Nights”), they go to their work, each busy with their own stuff (in terms of composition we danced separately, then lay down again, and then danced in contact with each other). The next day they’ve got a day off, and they go to the park, to the cinema, and afterwards he has trouble falling asleep while she’s sleeping soundly. That’s pretty much it.” And the dancers, our colleagues who were there among the audience, were laughing all the way down. However, there was truth in those words, too.

In this country there’s an understanding, a tradition even, that people doing arts or thinking they’re doing arts are some kind of apostles. Unlike mere mortals, no less than Poets and Citizens.

AA: In a way it was true …

SK: It could have been this way, right?

AA: Yeah. We didn’t use to think this way though, and when I come to think of it now – what if I did set this task now? I would be really interested in something like that.

SK: When we were choosing our outfits, we got an image: why don’t we get dressed like an ordinary couple from Canada. I don’t know where we got that image from…

AA: Everything to do with outfits was particularly touching for us, because that kind of thing comes easily. You put something on, and you get your message across to your audience. And it’s as if you might loosen up. I guess we were still fumbling with it at that time … Funny as it might sound, but after all we’re here, I mean Russia or CIS. In this country there’s an understanding, a tradition even, that people doing arts or thinking they are doing arts are some kind of apostles. Unlike mere mortals, no less than Poets and Citizens. By no means like ordinary people, say, doctors or dressmakers. And the moment this so-called dialogue with the audience emerges (and the need for it has always been present), there’s a stance like “well, honestly, what can you ask me? It’s too subtle and sophisticated for you anyways.” I remember my own powerful ruminations on all those so-called conversations. On the one hand, you are curious about what people have to say, but really, it’s only positive feedback that you welcome, and the rest goes unheard and, what’s worse, is something you’re so dead set against that you say they just got you wrong.

SK: … you didn’t get it right…

AA: … you got it all wrong! What I’m doing is good stuff.

SK: … if you didn’t like it, you just didn’t get it.

ON AUDINCE AND CRITICS

Anna Kravchenko (AK): Well, it is really hard to keep any kind of discussion going when you feel there is no involvement.

AA: Exactly, when there’s a lack of interest. It’s all about keeping the shuttlecock flying from one side to the other, isn’t it? It’s not like “wait and see me strike, I bet you won’t be up to it.” However, it’s always been like this: I’ll strike it really hard, I’ll show you, you’ll be at your wits’ end. Oh the performance I’ll put on, the subject I’ll take up!

AK: And what was it like for you at the very beginning, I mean your relationship to the audience? Did the audience matter to you, the way it took what you were doing or non-doing?

SK: Well, yeah, at the beginning it did, sure.

AA: It has always mattered.

SK: It has always mattered, and it’s always been very emotional.

AA: Now it’s different.

SK: Yeah, it is. Now you understand that it is always a win-win situation. And back then you felt you might lose… It’s a fear, it’s just a fear. You’re doing what you believe in…

AA: … and you are really afraid that the audience won’t accept it.

SK: Because you somehow depend on it. If they don’t accept it, if nobody likes it, what to do next?

AA: Why live?

On the one hand, it made us feel like we had know-how. After all I’ve been taught this for 5 years, and I’ve excelled at it, too! But on the other hand, I felt a tremendous amount of resentment over not having received any professional training in dance or choreography.

KG: It gives you a way to define yourself, and if your work is not accepted, you feel like it’s you who’s not accepted.

SK: Yeah, you identify yourself with all this, especially at the beginning, because you’re taking risks. Now we are still very engaged but we don’t identify ourselves with it that much. It might have come with the experience, or there might be some other reasons for that change.

AA: There is an important point here. We’ve got drama training, so we spent a few years studying acting. On the one hand, it made us feel like we had know-how. After all I’ve been taught this for 5 years, and I’ve excelled at it, too! But on the other hand, I felt a tremendous amount of resentment over not having received any professional training in dance or choreography.

SK: If we got some feedback saying that we were great dancers, it sounded different to us than to those who had education in the dance field. For us it sounded like a super high level of appreciation, as we had always sensed we were not-quite-dancers.

AA: It still feels this way.

SK: We keep teaching others, and at the same time we keep learning how to dance, as we’ve never had that kind of training.

KG: So not having a degree didn’t set you free? In the sense that you haven’t been taught what’s right and so could do whatever you wanted?

AA: Not really. And keep in mind it’s this country we’re talking about, with its peculiar attitudes. You do contemporary dance, and what do people compare it with? It’s like you play ball hockey, and they saw only classical ballet. And they stick to certain preconceptions…

When we performed in New York in 2006 with a piece called “3petiX”, there was a review saying something like “an incredible technique, it seems there are ten people on the stage instead of two”.

SK: Yes, back then nobody in this country was aware that all Europe was already doing it. And the things that were unknown here and were being done in Europe excited us. We were really keen on that aesthetics, that perception.

AA: And we were hugely influenced by working with Sasha Waltz, of course. It has definitely made a strong impression on us, gave us an impetus.

SK: And we wanted to share it so badly. That partly accounted for imitation in our works.

AA: That’s s exactly what I’m talking about. We’ve seen awesome dancers, we’ve worked with them, they’ve taught us things, and it’s all been a pretty amazing experience. You can’t help being influenced by it, and it’s a long-lasting effect.

SK: When we performed in New York in 2006 with a piece called “3petiX”, there was a review saying something like “an incredible technique, it seems there are ten people on the stage instead of two”. And we felt like “Finally!” And it was an American critic! While here at home the response to that piece went like “It’s some kind of weird plastic theatre, not a dance really”.

AA: They were saying, “They are not bad actors, but what about dancing?”

That’s why for 25 years half of the audience has been oblivious to contemporary dance as an art form, because many people judge by what they read.

SK: Which leaves us wondering when we will be able to have this kind of reception, how long it is going to last.

AK: Was it really worth waiting for the time they would call it a dance? Shouldn’t you have taken it easy, having called it a performance? You could have hidden behind this concept, in a way.

AA: That’s too much trouble. We might as well just have lightened up. Because the people producing concepts of this kind (and I do not intend to offend these people) are always running late. They are twenty, forty, fifty years late, honestly. Even compared to the audience that comes or used to come they are late. Say, there’s a girl who used to pursue folk dance and then quit because of an injury and took to writing reviews. In fact all her critical reflections had to do with her own disability. And her speculations were passed on to a huge number of minds, that distorted notion that contemporary dance is something that is reviewed by a person who’s unable to dance. That’s why for 25 years half of the audience has been oblivious to contemporary dance as an art form, because many people judge by what they read.

KG: Well, that makes sense. If you have trouble grasping the subject, you turn to reading.

SK: You know, what’s interesting is that they stopped writing about us the moment we stopped caring what they write. I guess we haven’t received a single review for the last five years, though we do produce two or at least one work every year. No critics ever come to our performances at all.

AA: They do not come to watch, it’s their job, there’s nothing wrong with that.

“Oh my God, our neighbors put on that awful stuff again!”

AK: Which means there’s a lack of genuine interest.

SK: The last review we received was of our work called “Probability practice” (“Praktika veroyatnosti”).

AA: Sonya Levin’s mother wrote a very good review.

SK: It’s funny, because the first two articles on that piece were written by critics who had always reviewed all the performances, including some of ours. They were hideous, those reviews. They went like, “they walk, they do not dance, did they really have to take their clothes off”, etc. It was total absence of analysis.

KG: They were done from the standpoint of the world they live in.

AA: Yes, something like “Oh my God, our neighbors put on that awful stuff again!”

SK: And Sonya’s mother just couldn’t stand it. She used to work as a theatre critic, so she wrote an article analyzing the performance itself and all the comments on it.

AA: She did it professionally, and we’re not saying it because she was there for us. Anyway, at that time we were about to give up those games… We were just having some fun.

ON MEANINGS AND NOTIONS

AK: I wonder how you experienced it. We discussed how others saw it, and what’s the insider’s perspective on your work? What notions did you stick to at that time and where are you now?

SK: It’s quite ambivalent. It’s all interconnected. However, I’d say that before the transformation we had stuck to the notions of language, the language of dramaturgy, dramaturgy in a very specific sense, of course. Since then we’ve been working with the notions of movement research, which are quite different from the notions of language or search for language. Now it’s more of a mystic experience related to space and time. On the other hand, research means something that brings us closer to the concepts of technology and method, which are somehow integrated into each other. We are not much of technology fans though, technology in its pure form. It’s just that sometimes it could be very useful as an exercise, while it’s inseparable from the field of your personal perception.

One would prefer to think that the performance was about a couple’s daily routine. That’s what makes one feel at home, that’s something one might identify with.

AA: We ended up turning our gaze rather inwards, inside ourselves. It doesn’t mean we closed off. It’s just that the most efficient technologies and systems ever developed are within us. “How do I do this?”, “What do I do?”, “What if I do it this way or that way?” some very simple things. How do I put things in sequence? What do I do first? Do I take my shoes off first or wash my hands? And it wasn’t about any deep psychological analysis either; it was a way to observe our response to the surroundings. And I agree with Sasha about it all being so interconnected. My body reveals my way of living, the things my life is made up of. It’s so explicit that even if you can’t get hold of it mentally you might still be able to feel it bodily. When you’re watching yourself and suddenly realize your movements tend to be of certain amplitude, or incline towards this or that.

AK: You said it’s something personal, and if we take this word as a point of departure, we’re likely to think of our childhood, our life experiences. And dealing with this personal stuff you ended up getting at very abstract notions. It is interesting how it works. How does personal stuff lead you to arrive at the deep level, the level of being? It seems very common, something anyone can relate to, but it’s hard to deal with. One would prefer to think that the performance was about a couple’s daily routine. That’s what makes one feel at home, that’s something one might identify with.

SK: And it’s more of an effort to bring the two things apart, to see that there is time for this and time for that.

AA: A friend of ours once saw our performance “M23″. He is a kind of avant-garde theatre director, and he made quite an amusing comment on it, “That’s cool! There’s a man and a woman, and there’s love between them.”

SK: No concepts, just “Cool!” But at the same time it was a sham, we weren’t dressed as a man and a woman, I mean we had no such markers in the performance, unlike in “Days&Nights”. “M23” had to do with observation. It was a challenge, a continuation of the research we did in “Days&Nights”. What is it like when one moves and the other just watches?

The worst thing we heard in recent 3 years was “I don’t get it”.

AA: We ran workshops and could observe our colleges observing other people perform, and it was fascinating. After all there are not so many people you can look at for a long time. I love watching Sasha, and I thought it would be great just to sit down and watch her.

SH: And that’s how we stirred up a multitude of new layers, they were set off spontaneously. We did some solos connected with this idea of observing, observing yourself or something else. We ended up with an infinite matryoshka of someone observing someone observing oneself etc. And people said, “What a touching story on a family relationship”. Well, there must have been something of this kind as well.

AA: Everyone sees what he/she is willing to see. But my interest lies elsewhere. What I’m willing to do – and what means coming back to myself, what really fuels me, and what I’m working on – is to draw out this thing that wants these kind of movements, this kind of attention, or wants to agonize a little in public. And there’s a whole lot of other aspects.

SK: At some point it’s became so easy to elicit these kinds of things. Perhaps we don’t identify with it the way we used to. And still there’re a lot of feelings about it. It’s so much easier now to start doing something, as you don’t care how others will react. Reflections on it have changed, too. It’s amazing! It might be a coincidence, but not necessarily. The reflections of the audience have become more to the point recently. The worst thing we heard in recent 3 years was “I don’t get it”.

AA: “I don’t get it” is neither good nor bad. It’s just how things are at the moment. There’s nothing wrong with that, you don’t have to understand. How did it make you feel? Did you feel anything? How about that? It is not about understanding. Of course people want to be understood, but it doesn’t mean the work they do has to be understandable. These are different things.

ON WHERE “IT ALL COMES FROM”

AK: At some point of your artistic practice you founded a company called PO.V.S.Tanze. The notion of “a company”, what did you need it for?

SK: At that time it was just something we did to assert ourselves, given the circumstances. Up until then PO.V.S.Tanze had been the name of an independent group we were part of, the group of people collaborating on different performances, exhibitions, and music production in the 1990s. And while we were with Sasha Waltz we got a grant from the Goethe-Institut and decided to do a performance of our own in a small group.

AK: Who was in that small group with you?

SK: Lena Leniger (previously Lena Golovasheva), she is based in Germany now. Zhenya Kozlova. Taras Burnashev performed in the second piece and designed costumes for the first one.

It really was collaborative choreography, and we were on equal terms as we all came from a place where this was taught. It wasn’t always like this as other people were coming to join us. At the beginning, however, we were equals, we had a similar background, so we were spared from having to talk over the basics.

AA: All those people had been in Gennady Abramov’s Class of Expressive Plastic Movement (at Vasilyev’s School of Dramatic Art), and when it had come to an end we decided to set up something of our own, which also closed down later. We followed different paths, having accumulated a certain amount of joys and grievances related to working together. So everybody embarked on their own journeys. And afterwards we were able to ask people to join in. And that felt cool, being a part of Po.V.S.Tanze (in Russian “povstanze” sounds like “rebels”) as opposed to newcomers. It was funny, this self-identification stuff, because in fact I didn’t do anything to call myself by this name.

KG: Well, when you talked about all those issues of fitting into a context and the desire to hold on to something, the founding of a company protected you in a way.

SK: It surely gives you a feeling of community, artistic collaboration. Abramov taught us to keep sorting things out within ourselves. So our group was made up of truly independent personalities. It really was collaborative choreography, and we were on equal terms as we all came from a place where this was taught. It wasn’t always like this as other people were coming to join us. At the beginning, however, we were equals, we had a similar background, so we were spared from having to talk over the basics. We didn’t have to work out what “collaborative” stood for, who the leader was, or who would tell us what to do. We were brought up within the structure where things like that were self-evident. Besides, having worked in Europe gave us a lot of technical instruments. We learnt how to select, how to create a structure. As for language, life, moment, improvisation, acquiring a movement – that’s what Abramov taught us.

And it was so contagious it made you believe after a couple of more classes you’d be able to walk through walls.

AA: Gennady Abramov was a prodigious man. It had been an incredible blend. First, Vasilyev’s School, being in this particular framework, in this particular country. A very special location. And inside it there was a very special man Gennady Abramov, with his know-how, his technique. He had a very rigorous understanding of life and the role of an artist, endowed with superhuman aspirations. And it was so contagious it made you believe after a couple of more classes you’d be able to walk through walls. And that fervor was with us for years. Now we see it as, say, a monarchy, which is deep-rooted in this country.

SK: Both of them, Vasilyev and Abramov, were kind of monarchs that wound up clashing… The European project that came afterwards was a completely different experience (ref. to Sasha Waltz’s project “Na Zemlje”, 1998-2001). We didn’t lose any of Abramov’s fervor, so we kept on thinking how cool and unique we were, and at the same time it struck us that we amount to nothing as dancers. We were unable to repeat a dance phrase. We couldn’t dance at all. After Abramov’s ivory tower we went straight to the factory. So we got down to learning how to dance. Thanks to Abramov we knew how to think with our bodies, but we didn’t know how to dance.

We survived, we didn’t lose interest in what we were doing, and we thanked Abramov for that.

AA: We were being paid for it, too.

SK: It was other super training for us, very different one.

AA: It was different and yet the same. It was another dictatorship, and a harsh one. Afterwards we had another communicative experience with people who left Russia years ago and now live in Germany, DoTheatre. It was a mind-blowing experience. We went together to Edinburgh International Festival, and we had 21 performances in a series. We survived, we didn’t lose interest in what we were doing, and we thanked Abramov for that. The setting was so much different. There isn’t much space to search for something new. You have to repeat the moments that worked, because people are willing to pay for it.

ON A MYRIAD WAYS

AK: I guess it’s hard not to cling to what once worked. As you said, when you have created a method that helped you do a piece, you are unwilling to break away from your creation.

AA: And what was so cool about that creation of mine? It’s just that I’m aware that it made me feel great… It reminds me of a photo album. We’ve got lots of them – we used to take pictures of everything and collected all those pictures. And I strongly dislike what I see in these pictures. I see myself, and an absolutely different self.

SK: By the way, it’s surprising. At our age people tend to admire themselves in those photos, “look how young we were”. In our case it’s the other way round. We look at some pictures we took ten years ago and go like, “What’s that?” We’ve never been fat, but we look at ourselves and feel like there was some kind of excess. We don’t have it now. We see it.

AA: I’ve got some photos I like to look at, of myself in the army or with my Mum. When I look at them it’s like I’m changing, something is going on inside me. This image does something to me, and I want to keep it with me, to follow the changes I undergo.

And that’s where you can grasp something essential about yourself. Because what you get to know afterwards has to do rather with the context than you.

KG: I also like to look through the pictures of me as a child, but only up to five years old, and I simply can’t stand later pictures.

SK: Because you felt like something was emerging at that moment.

KG: Yes, like a myriad ways were there.

SK: And that’s where you can grasp something essential about yourself. Because what you get to know afterwards has to do rather with the context than you.

AK: And look at us, coming up with this anniversary stuff. Does it mean it is not interesting to look into the past as a pile of photos, to put it roughly?

AA: See, it is great that you came here to ask the questions that matter to you. And I enjoy this conversation. Let’s say it’s our anniversary, why not? There’s a good vibe, and you can’t force things like that. So we’ve got to enjoy them.

SK: And I keep recalling the people we met and worked with, feeling them, thinking about them… I believe there is something significant to it. We crossed paths at some point…

KG: … the point of a myriad ways open.

SK: Yes, it was a crossroads. It wasn’t a random thing, either. And we traveled part of the way together, which is great to look back on.

AA: There were no come-and-go people, everybody was extraordinary in a way: Elena Leniger, Evgeniya Kozlova, Taras Burnashev, Olga Vavilova, Nataliya Krutilina, Anna Subbotina, Nina Kungurova, Olga Sytnik, Ilya Belenkov, Alexander Andriyashkin, Sonya Levin, Emmanuelle Gorda, Alyona Smirnitskaya, Vladimir Sturov, Irina Dolgolenko, Larisa Alexandrova, Daria Buzovkina, Irina Gonto, Stanislav Klimushkin, Ilya Malkin, Brad Aldous, Richardas Norvila, Valery Vasyukov, Arkady Marto, Vadim Koptievskiy, Mila Raketa, Nick Artamonov.

In 1997 in Moscow several more or less independent dancers organized a group called Po.V.S.Tanze which means “almost inwardly free dances” as the abbreviation goes, while the word as a whole means “rebels”. It was an experimental project in the field of dance performance and improvisation. A successful performance at the international festival “Pushkin & Goethe” in 1999 in Moscow encouraged them to create a professional dance group. For 15 years Sasha Konnikova and Albert Albert have been the core of the company. In 1998-2001 they worked with German choreographer Sasha Waltz. Previously they studied contemporary dance, improvisation and performance in legendary Gennady Abramov’s Class of Expressive Plastic Movement (Anatoly Vasilyev’s School of Dramatic Art). Po.V.S.Tanze performed at different contemporary dances festivals in Europe, USA, and Israel. They created performances M23, Probability practice, Days&Nights, 3petix, &, and a lot more. Albert and Sasha took part in international projects as choreographers, moderators and performers.